Click on Image for an expanded view with image description and artist's comments

How It Started, How It’s Going

Open Door XVI Juror Statement

I don’t envy curators. I’m normally on the other side of this equation: with the artists, the ones putting ourselves out there, risking (and often receiving) rejection with every gallery application, every show proposal. The processes can often feel opaque; the decision-makers secluded, out of reach above the gates they keep. In the end, they are given voice in the form of administrative emails that either brim with hearty congratulations or unfortunately, regret to inform you. Those emails always seem to come late in the day, the key phrases always buried somewhere in the fourth or fifth sentence. As tough as they are to get, however, I realize now they can be even tougher to send.

And that’s because jurying is a difficult gig. I was honored to be asked by Rosalux to jury this year’s Open Door and was blown away by the volume and quality of work to choose from. It was also pretty intimidating: over 340 artists submitted up to three works each, leaving me to pick a mere 36 pieces out of close to a thousand. In essence, you’re trying to weave a cohesive fabric out of hundreds of disparate threads, to create a chorus out of individual voices. But let’s not be overserious here — it can also be a lot of fun.

Knowing that this show would only live online and in print, selected works had to pack a punch on screen, as is — size and scale would not be as much of a factor as they would in a physical installation. Good photos were a must. Other than that, I dove in with no preconceived concept, just open eyes and an open mind.

But a theme emerged. This long, strange year has changed something inside each one of us. We’ve all borne witness to an uprising against systemic bigotry and brutality; to a pandemic that has exposed so many rifts and so much resilience; and to a political system that seems to be on life support itself. We’ve all felt 2020’s unique cocktail of confusion, fear, anger, and hope course through our bodies. No surprise then that much of the artwork submitted this year reflects that. There were many images of masks, of windows and blinds, of domestic scenes with food and family. Interior and exterior spaces — both physical and psychological — took on new meaning as places of refuge or melancholy. And abstractions emerged that called to mind chaos, stillness, isolation, and interconnection.

Another aspect of curation besides simply choosing the works is putting them in conversation with each other. At this point I started thinking of the show as a mixtape, about creating a deliberate, linear journey that might chart the ups and downs of this year’s grueling rollercoaster. A good place to start is Monday, Sara Suppan’s deadpan oil painting of Garfield, resignedly frowning through his own personal thunderstorm in spite of the clear skies above. It’s a hilarious use of a serious medium, recreating with great skill a simple, slapped-up sticker. But it also captures a moment of rueful individual torment, of a cartoon avatar concerned solely with his own suffering. The stormcloud motif continues into Carolyn Reed Barritt’s Folly, a mixed media drawing that churns with tight, expressive strokes just barely contained on the page. A solid mass of grays, blacks, and blues coalesces out of the wild marks, menacing and portentous.

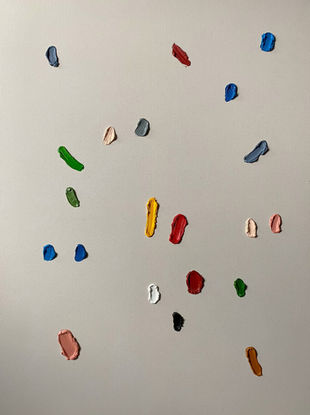

That sense of looming danger isn’t lost on the people in Philipo Dyauli’s piece, despite its cheery title: Come On In! The Water’s Fine! They don’t seem to believe it, preferring to stay on dry land in their bright swimsuits. The woman in the middle warily eyes three birds in the distance: seagulls, you’d be safe to assume, but on second glance they could just as easily be American eagles. From here, Jonas Criscoe’s Q*bertesque periodic table and Preston Palmer’s spacious paint daubs introduce a mixture of scientific and organic abstractions to the story. The many eyes of Ryan Peltier’s military commander bug out in response, and from there we’re off, into a sequence of scenes and sentiments that will feel all too familiar to those of us who’ve spent the past nine months living in and out of lockdown.

We all bring our own contexts to works of art, and we all find our own meanings inside them, sometimes in spite of the artists’ intentions. I hesitate to further impose my own interpretations so explicitly on your experience of these pieces, so I will leave you with the suggestion that you read this group of work like days on a calendar, meeting each piece on its own terms but also as part of a continuum. It’s a story that builds on itself as you go. You might recognize a friend’s face in a line of tar on the pavement. Your own anxiety in the menacing shadow of a Doberman’s growl. Time slipping by like plates of food falling off a table. The stresses of your city in broken windows and blooming flowers. There are passages focused on color, on form, and on narrative. Moments of accomplishment, exhaustion, sensuality, dignity, and indignation.

There are moments of formal ingenuity as well, like Derek Meier’s unorthodox intaglio embellishments and the subtle color variations Erika Ritzel finds in a ripped roll of toilet paper. Or when Epiphany Knedler’s threaded contrails blur the line between photograph and assemblage, between the size of a sewing needle and a scissor lift.

Near the end, we find Amy Usdin’s beautiful, intricate fiber work Anymore, a four foot wide green and brown mass of fabric and netting. Here on the page, though, the work reads like a mask, as frayed and threadbare as our nerves and our patience. Delaena Uses Knife provides the counterpoint, telling a hopeful story with her own hand-beaded mask: Covid-19 Survivor. That’s as real as it gets. The show’s final passage takes us from that realism through to abstraction, as the watery background of Kendra Bulgin’s Sing Second Hand Sorrows gets reflected and inverted in Darren Oberto’s placid Faceted #20, before tessellating out to infinity in a burst of cyans and pinks in the final piece, Michelle Curio Cañada’s Window.

Introducing the whole series was Alora Clark’s The Cost of Living, a simple but impactful pattern of block printed skulls and coins that reflects the tragic algebra this year — and this system — have forced on us. The personal and political choices we faced in this year (and in so many before) have asked us repeatedly to weigh the value of human life against that of human industry.

Cañada’s Window leaves us with another pattern, this time in full color instead of black and white. It’s a visualization of interconnectedness, a combination of rigid geometry and painterly impasto that, for me, weaves together all of the individual stories told here into one final, vibrant patchwork.

My hope is that, for all the pain this year has caused, we move forward wiser and kinder and stronger, ready to put in the work that will collectively turn our fortunes around. You can see that energy, that magical and necessary empathy, in the artworks collected here, in what I hope will be a document to look back on for inspiration. A 2020 mixtape to help us remember how it started as we look for the truth in how it’s going.

-Russ White